News

Billionaires Come Together Under The Giving Pledge Vision To Give Back To The Worlds list

December 29, 2021

July 29, 2024

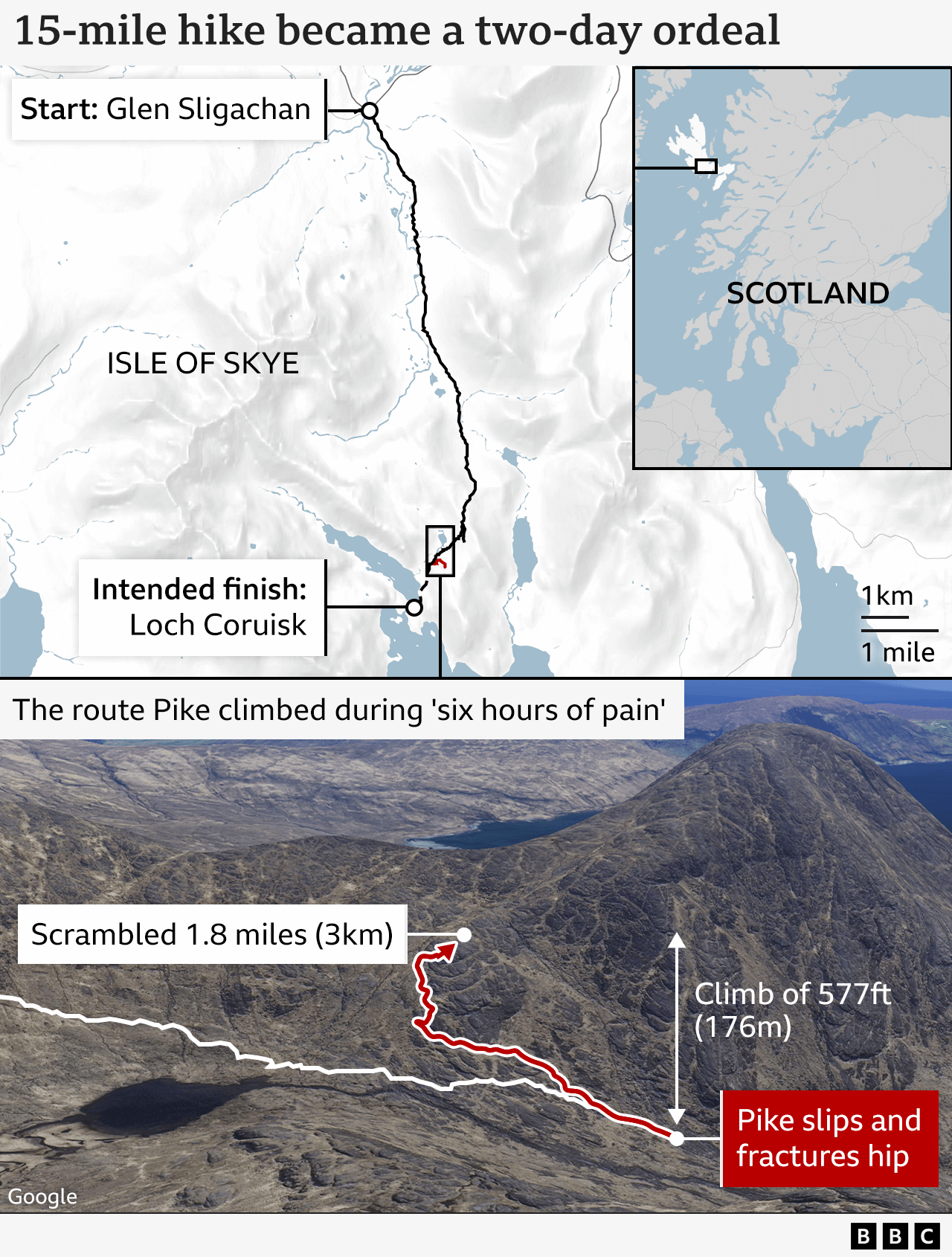

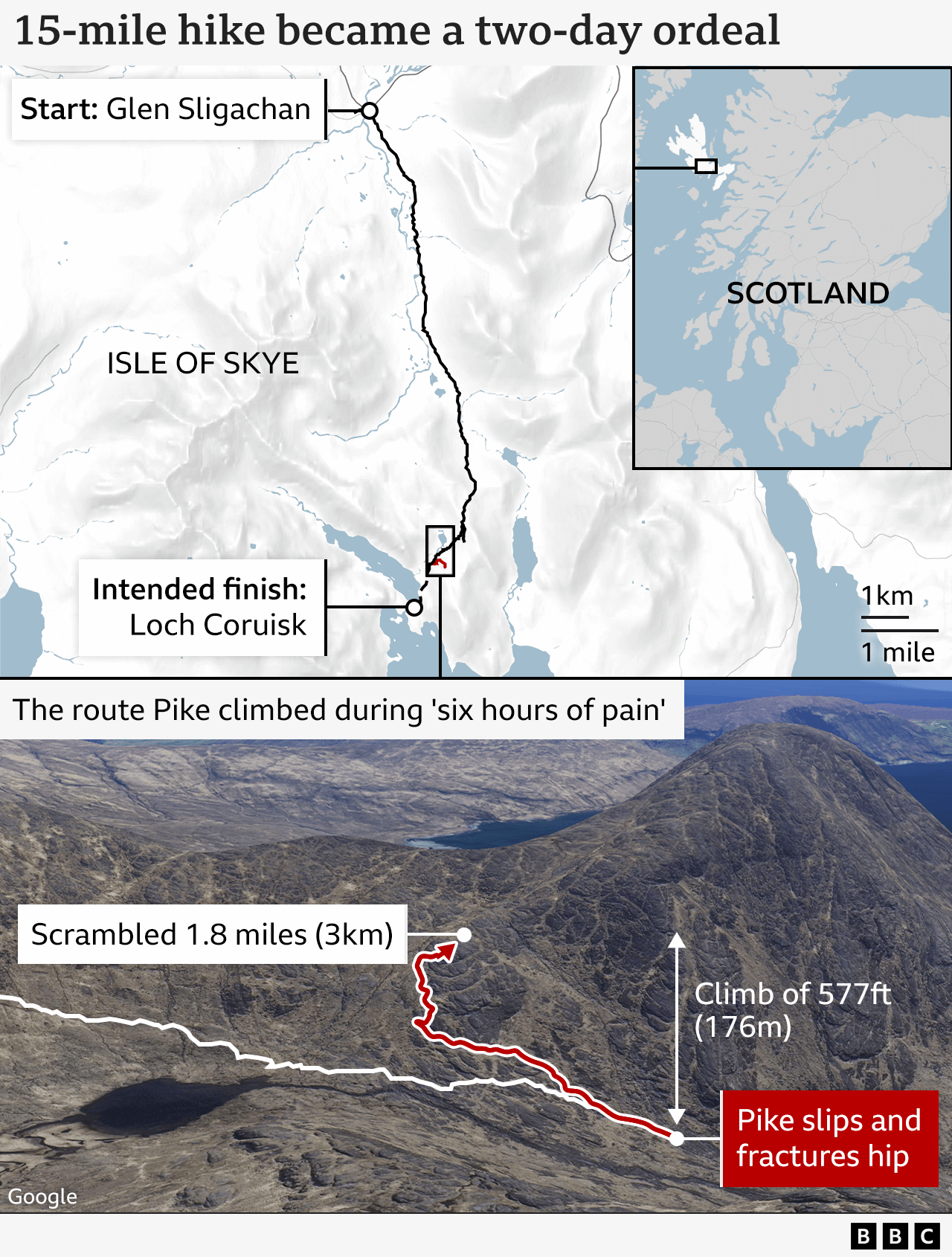

At about 7:30 GMT on 16 February last year, John set off from a B&B in Portree to begin a 15-mile (24km) hike from Sligachan to Loch Coriusk and back.

A keen walker from Bristol, he planned to spend the last day of his holiday completing the roughly eight-hour round trip.

The very flat terrain of the first six miles (10km) proved no issue on that Thursday morning and there was nobody around as he took photos of the unspoilt scenery.

But on the approach to Loch Coriusk, he came to a mountain pass - a grassy bank punctuated by smooth black rocks that became slippery as it began to drizzle.

“On the GPS device, it [the route] looked like a completely straight line, but it wasn't... there's no path,” John said.

“And I didn't like it at all. It was very, very difficult to follow.”

As John walked over the rocks, he slipped “in the flick of an eyelid” and his hip hammered against the ground.

“I was in a lot of pain immediately," he said. "I thought this doesn't feel at all good, but I thought, ‘It's midday, I'm going to have some lunch and then I'll let it settle down'."

After trying and failing to stand up, John diagnosed himself with a hip fracture.

The black gabbro rock John slipped on, which became slippery when wet

With no civilisation for miles and no signal on his phone, he decided his best option was to try to reach higher ground.

Over the next three hours, he scrambled on all fours for 1.8 miles (2.9 km) and eventually reached a position 577ft (176m) further up the mountain.

“It was obviously painful and it was still quite a steep climb,” he said.

“When I got up there, I couldn't get signal there either and my GPS device was swinging all over the place. I thought, ‘I need to get back to the path’.”

John spent the next few hours sliding back down the mountain, passing goats that were “the only sign of life” he had seen all day.

With the temperature dipping to 1C overnight, John was left shivering in a foetal position. He soon realised that by shaking himself, he would generate more heat to keep warm.

“I was panicking from the outset. I obviously realised I could die,” John said.

“I thought this is actually far worse for my family... at least I know that at the moment I'm safe.”

As a Christian, John said he had turned to prayer and later learned others had prayed for his survival too. He described feeling “the sensation of a very close presence”.

The next morning, the landlord of the B&B raised the alarm when he realised John had failed to check out.

Police in Portree alerted their counterparts in John’s home city of Bristol, and Avon & Somerset officers went to interview his daughter.

"She was able to tell them from Find My iPhone where I'd last been seen [on the app],” John said.

While rescuers now had a starting point, they were still searching an enormous area.

It was the discovery of a different digital footprint by John's nephew on Friday that would prove to be the decisive moment in the rescue mission.

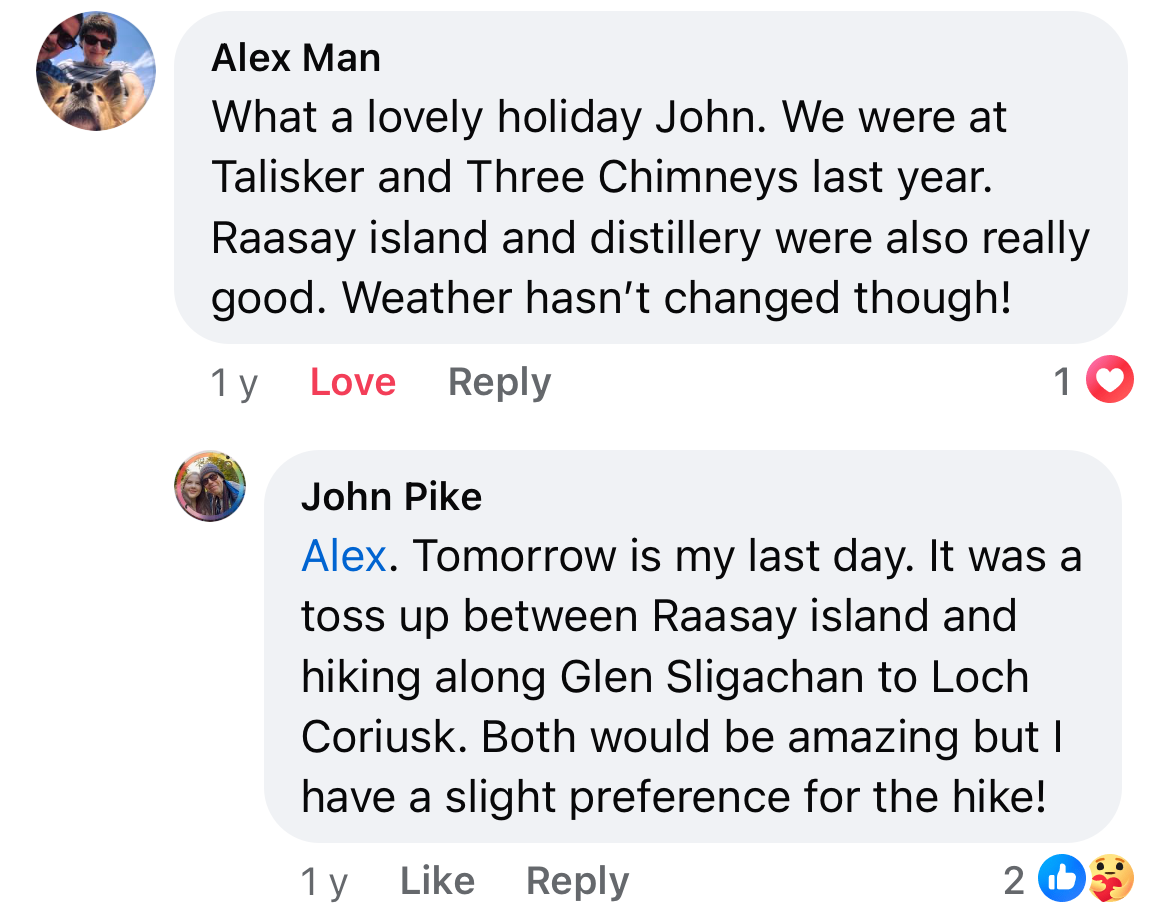

The day before setting out on the hike, John had posted on Facebook and taken a moment to reply to a friend's comment about the trip.

What might have been a ordinary exchange on any other day became crucial information for police in narrowing the search area.

More than 50 rescuers worked through Storm Otto on Friday, despite winds of 95mph (152km/h), sub-zero temperatures and snowfall.

Teams from the Kintail area, RAF Lossiemouth, Police Scotland Highlands and Islands Division, Search and Rescue Dog Association Southern Scotland, the Coastguard and Mallaig Lifeboat all aided the rescue effort.

Around 14:00 GMT that day, a helicopter had flown over the ridge above John before turning back on itself and flying away.

It was then that he realised all his clothes were black or navy, effectively camouflaging him against the dark rocks.

His hopes of being found were raised and dashed once more when a helicopter came back just before 18:00 GMT.

John waved a white linen bag in the air and blew his emergency whistle, but to no avail.

“That really was a very low moment,” he said. “I thought, you know, I'm 61, I've had a good innings... If I do go now, I've achieved a lot.”

It was thinking about his daughter, a first-year university student who lived with and relied upon him greatly, that kept him going.

While John continued to wonder whether help would ever come, rescuers had set out on Saturday morning to search an area where they now believed he was most likely to be found.

Ian Stewart, the first man from Skye's mountain rescue team to approach John, recalled the moment he heard his whistle.

"We kind of stopped and then we radioed the RAF, who were the other team out, and said, 'Did you blow a whistle?'. They said, 'No'. And then we were listening for that whistle again," he said.

"Then we heard it and we were trying to work out the direction it came from because as far as we were aware, there was nobody else on the hill.

"One of the guys on our team who was very sharp-eyed, he spotted what he thought was movement quite close to the path."

Ian had not expected John to survive the storm but he was still breathing when the team sprinted over and found him curled up in a ball, "indistinguishable from a rock" in his dark clothing.

"To find him alive when you're probably expecting to find a body, it's a real buzz," Ian said. "I was elated."

Scottish Mountain Rescue (SMR) said it was difficult to quantify John's chances of survival, taking into account the length of time he had been missing and the weather.

Its statistician Jessica Steinemann said: "John's story is quite unique given the length of time he had been missing and exposed to the elements, the time of year this happened, and the storm that happened at the same time."

She said most missing people were found by SMR teams after one night outside, often uninjured and during the summer when a larger proportion of incidents were reported.

The majority of those involved in mountaineering accidents who were missing for multiple days did not survive their injuries, she said.

John's story highlighted the importance of "letting someone know where you're going, when you're expected to be back, and what people should do if you don't report to them," she added, noting the B&B owner's raising of the alarm.

When John heard of the recent disappearance of fellow doctor Michael Mosley, who had been walking alone on the Greek island of Symi, it brought his own experiences to mind.

"It just makes me realise all over again just how incredibly lucky I am to be alive," he said.

"There was an awful lot of criticism of Michael Mosley for going out for a walk without his mobile phone, for example, and in extreme heat. And I thought, ‘You guys give the man a break’. It's very, very easy to be wise after the event.

"He's obviously a highly intelligent man. You know, if he can't get it right, what hope is there for anyone? And yet it just happens to people.”

John's advice to fellow hikers now? "Leave a message in the front of your car on your dashboard saying where you've gone walking, as well as having told somebody... how long the walk is likely to last," he said.

"Have another method of navigation... I would strongly recommend to people having a GPS device with a full scale map of the area that you're walking in."

Ian added: "Just go with orange [clothing]. You look a little bit louder down the high street, but you're easy to find."

Anyone who finds themselves in need of assistance in the hills or outdoor spaces, or who is concerned for someone who has not returned from a walk, should call 999 and ask for the police and then mountain rescue.